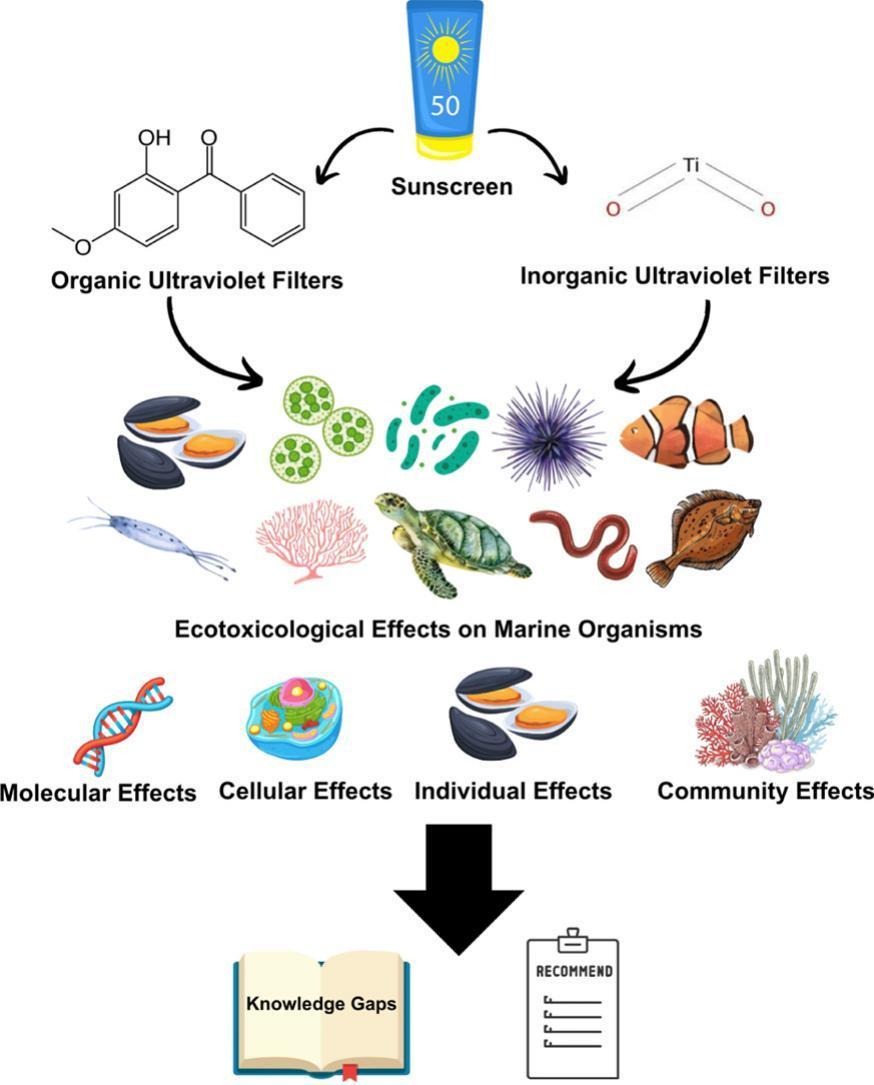

A new study published in Marine Pollution Bulletin highlights the significant impact of sunscreen on marine ecosystems. UV filters, present in sunscreens and other everyday products, reach the seas through various routes, contaminating water and organisms. The research highlights the need to further study the toxic effects of these substances and to adopt solutions to mitigate marine pollution

With summer just around the corner, most of us are gearing up to protect our skin from the sun’s rays. However, what is protecting us may be inflicting widespread harm on marine ecosystems. A new study published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin reveals significant knowledge gaps in the environmental impacts of chemicals found in sunscreens.

UV filters, which help shield skin from harmful ultraviolet rays, aren’t only present in sunscreens but are also used in cosmetics, paints, plastics, and cement. With worldwide usage being so extensive, it’s estimated that 13 to 31 million pounds of UV filters enter the oceans every year, with their impact on marine life largely untested.

How does sunscreen enter the ocean?

UV filter pollution occurs in several ways. The most direct is direct contact with water—when swimming, at least 25% of sunscreen is rinsed off into the sea. Indirect routes also apply: washing towels used to dry off after applying sunscreen, showering after a beach visit, and even urination contribute to pollute. That is, chemicals from sunscreen find their way everywhere, even into pristine-looking locations like the Arctic and Antarctica.

Effects on marine life

@Marine Pollution Bulletin

UV filter chemicals are toxic to a wide range of marine life. Current studies prove that certain chemicals, such as benzophenone-3, are endocrine disruptors of corals, fish, and mollusks, affecting their growth and reproduction. UV filters are also “pseudo-persistent pollutants” as their continuous release in the environment ensures their long-term persistence, worsening the problem.

One of the most troubling effects is on coral reefs. Some organic UV filters, such as oxybenzone, have been shown to contribute to coral bleaching and death, which further threatens reefs already stressed by global warming and ocean acidification. And it doesn’t stop there—these chemicals can bioaccumulate in the food chain, finding their way into fish and shellfish, with unknown implications for human food safety.

Ineffective filtration technologies

Among the concerning characteristics is the difficulty of eliminating the UV filters in the ecosystems. The wastewater treatment plants are unable to effectively eliminate these chemicals, and they find their way into rivers and oceans. Even ozonation—a highly advanced purification system—has been demonstrated to be incapable of degrading numerous of the UV filter chemicals.

It’s not just seawater that’s affected: UV filters have also been found in agricultural soil through the use of sewage sludge as fertilizer. That means that these chemicals not only pollute water but can also make their way into our food.

The research highlights that there is still limited research on the environmental effects of sunscreens. The majority of studies have been directed at tropical seas, with little attention given to temperate and polar oceans. Additionally, many studies rely on laboratory experiments with individual compounds, but in the environment, these pollutants co-exist with numerous other substances with which they may synergistically increase their toxicity.

It is necessary to continue researching the long-term impacts of UV filter exposure, to establish how these chemicals migrate along the food chain, and to assess their impacts on the different developmental stages of marine organisms.

Possible solutions: protecting skin without harming the ocean

The upside is that there are now more environmentally friendly alternatives to traditional chemical sunscreens. Mineral filters such as non-coated zinc oxide and titanium dioxide are less likely to cause environmental harm since they do not easily dissolve in water. However, one should ensure that they are not in nanoparticle form, as their potential toxic effects are not yet fully understood.

To reduce our impact, we can form simple habits: seeking shade during the hottest part of the day, covering up with sun-protective clothing, and applying reef-safe certified sunscreens.

Some countries, such as Palau and Hawaii, have already banned sunscreens containing coral-damaging chemicals. In the meantime, cosmetic brands are developing safer products with biodegradable formulations and sustainable packaging.