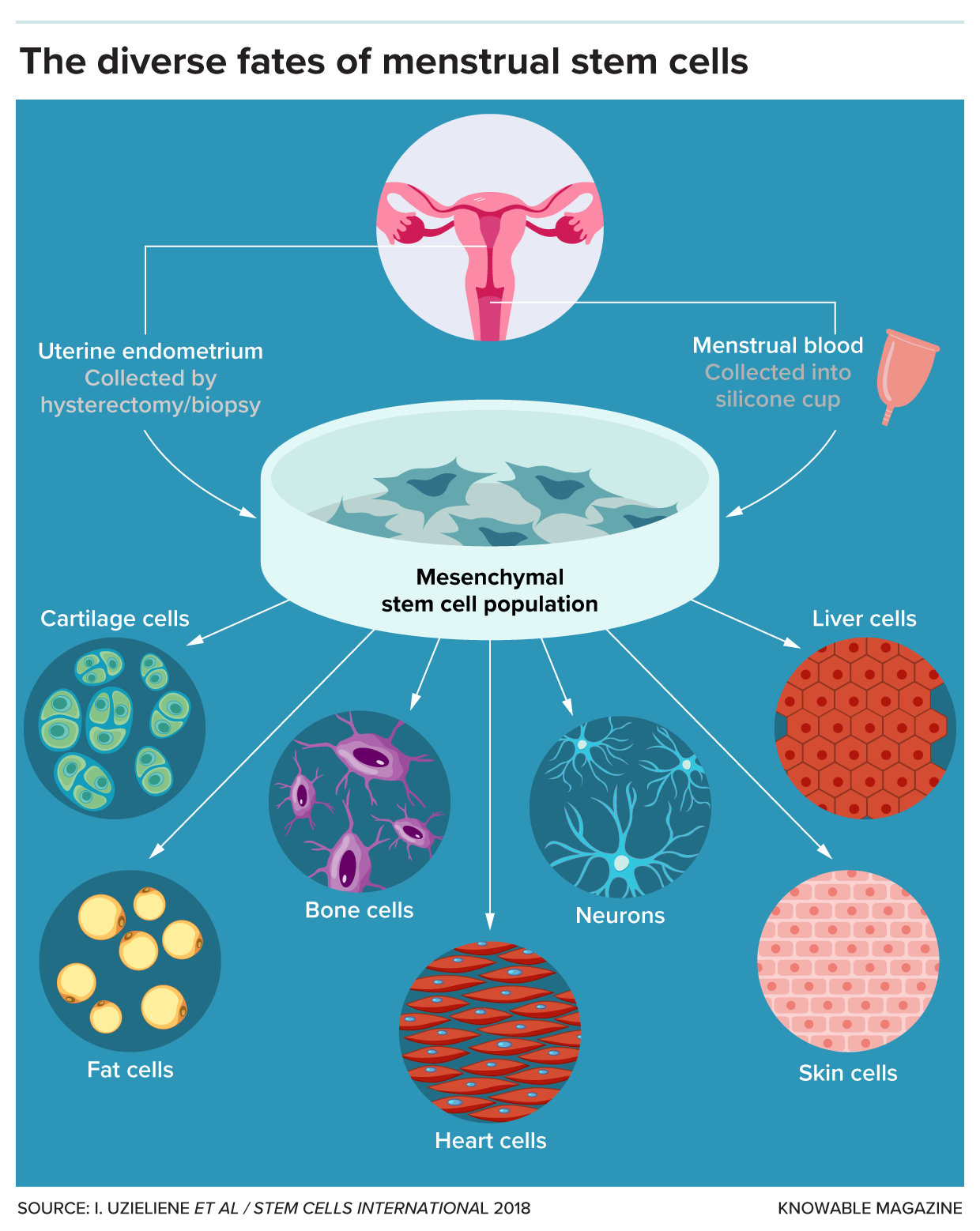

Long overlooked, menstrual stem cells could have important medical applications, including the diagnosis of endometriosis

Nearly 20 years ago, biologist Caroline Gargett embarked on a quest to find extraordinary cells in tissues removed during hysterectomies. These cells came from the endometrium, the lining inside the uterus.

Under the microscope, she identified what she was searching for: two types of cells, one flat and round, the other elongated and slender with whisker-like projections.

These were adult stem cells—rare, self-renewing cells, some of which can develop into various types of tissues. Gargett and other researchers had long suspected the endometrium contained stem cells due to its remarkable ability to regenerate monthly.

The endometrial tissue, which provides a site for embryo implantation during pregnancy and sheds during menstruation, undergoes about 400 cycles of shedding and regrowth before a woman reaches menopause. Despite isolating adult stem cells from many other regenerating tissues—like bone marrow, the heart, and muscles—scientists had not identified adult stem cells in the endometrium.

These cells are highly valued for their potential to repair damaged tissues and treat diseases such as cancer and heart failure. However, they exist in low numbers throughout the body and can be challenging to obtain, often requiring surgical biopsies or bone marrow extraction.

The whisker-like cells from the endometrium, known as endometrial mesenchymal stromal stem cells, are genuinely “multipotent,” capable of being induced to become fat cells, bone cells, or even smooth muscle cells found in organs like the heart.

@I. Uzieliene et Al / Stem Cell International

Since then, more detailed studies on the endometrium have helped explain how a subset of these valuable endometrial stem cells end up in menstrual blood. The endometrium has a deeper basal layer that remains intact and a superficial functional layer that sheds during menstruation. Throughout a menstrual cycle, the endometrium thickens in preparation to nourish a fertilized egg and then shrinks when the upper layer sheds.

Endometrial stem cells and endometriosis

Endometrial stem cells have also been linked to endometriosis, a painful condition affecting about 190 million women and girls worldwide. Although much about the condition remains unclear, researchers hypothesize that one contributing factor is the backflow of menstrual blood into the fallopian tubes, which transport the egg from the ovaries to the uterus.

This backward flow carries blood into the pelvic cavity, a funnel-shaped space between the pelvic bones. Endometrial stem cells deposited in these areas can cause endometrial-like tissue to grow outside the uterus, leading to lesions that can cause severe pain, scarring, and often infertility.

Studies have found that menstrual stem cells can be transplanted into humans without negative side effects. Researchers are also developing human therapies using endometrial stem cells—those taken directly from endometrial tissue rather than menstrual blood—to design a mesh for treating pelvic organ prolapse. This common and painful condition occurs when the bladder, rectum, or uterus slips into the vagina due to weak or injured muscles.

Despite the relative ease of collecting multipotent adult stem cells from menstrual blood, research exploring and utilizing the power of stem cells—and their potential role in disease—still represents a small fraction of stem cell research.

Additionally, cultural taboos surrounding menstruation and a general lack of investment in women’s health research can make it difficult to secure funding.

Source: NIH