The impact of the absence of the smartphone on the brain is surprising: it modifies brain activity significantly

Smartphones have been indispensable parts of our daily lives for the last few years, being employed for communication, work, and leisure. A recent study conducted by Mike M. Schmitgen of Heidelberg University, published in the journal Computers in Human Behavior, highlighted how withdrawal from this phone for only three days would significantly alter the brain activity.

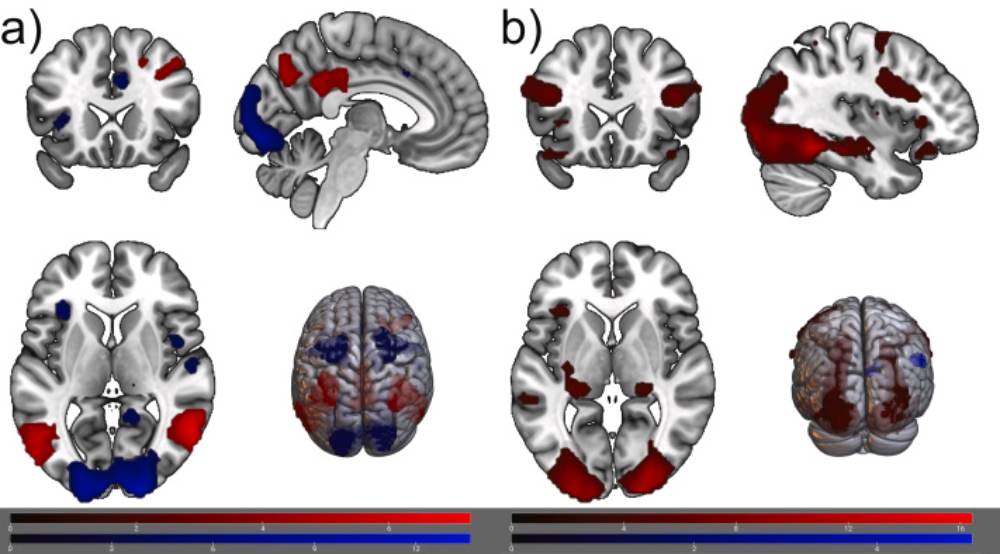

The experiment consisted of 25 young adults between the ages of 18 and 30 who were asked to restrict their phone usage to basic functions, such as emergency calls. Throughout the study, the participants performed specific tests among which was the functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), giving real-time assessment of brain activity.

The research revealed extreme changes in the brain, particularly those concerning reward mechanisms and addiction. The research revealed that the removal of the smartphone provoked responses similar to those seen by individuals who had suddenly ceased smoking or alcohol use.

Smartphone use could develop an alcohol and nicotine like addiction

Brain regions involved in regulating addiction showed changes within hours of withdrawal. The subjects at 72 hours were shown a group of pictures, some with frequent objects such as flowers and boats, and some with mobile phones. In these, the activation of the brain regions involved with reward and wanting happened, similar to the process of substance addiction.

This observation suggests that cell phone use could create a kind of addiction similar to that resulting from alcohol and nicotine. So, the fact that one cannot stop using the phone is not merely a matter of convenience or habit, but has a certain neurological foundation.

The aim of the study is not to demonize technology, but rather to raise awareness about the importance of mindful smartphone use. Their constant presence in our lives can influence our brains in ways that are often underestimated. Gradually reducing screen time may be a helpful strategy to rebalance our relationship with technology and promote better mental well-being.

Source: Computers in Human Behavior