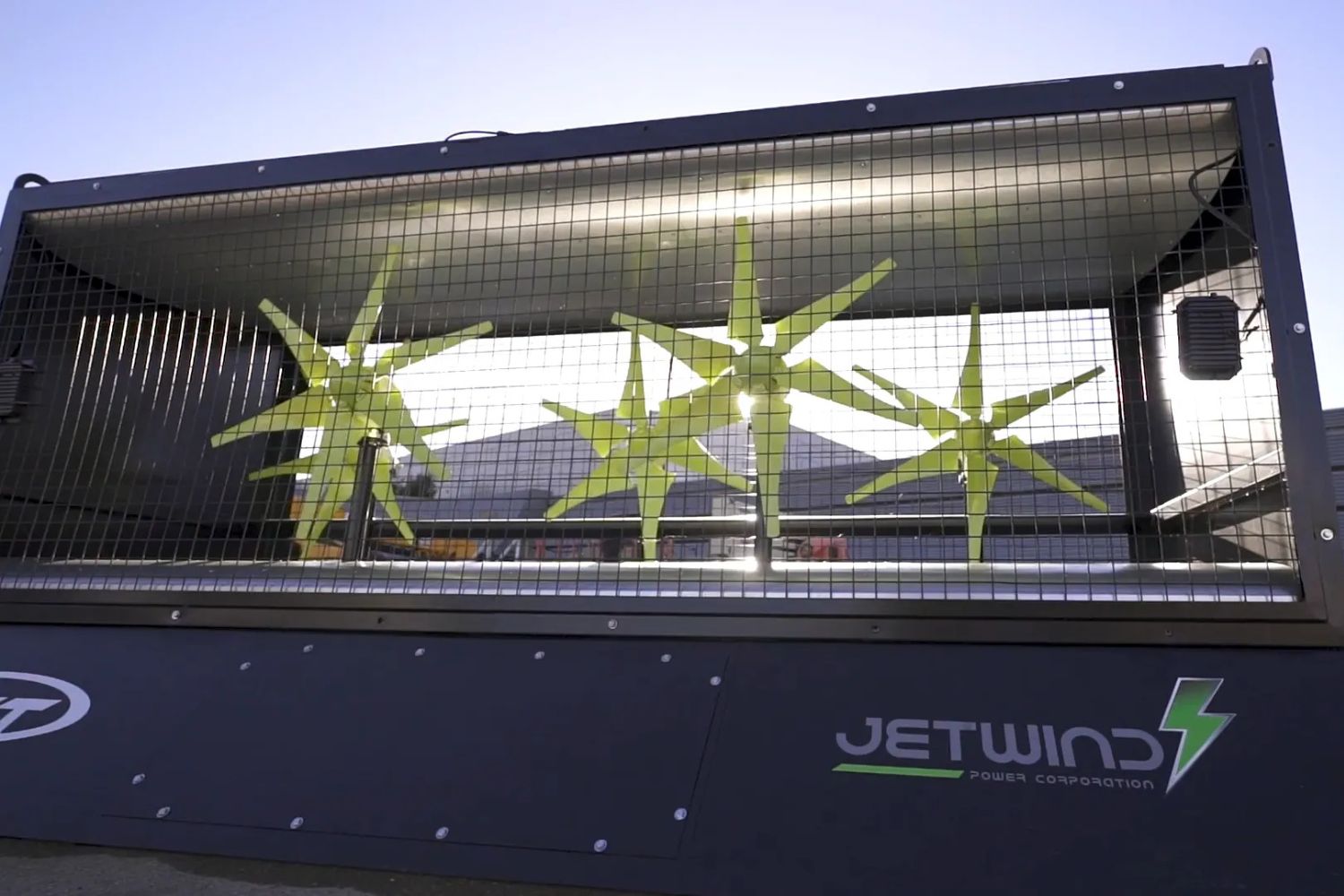

Wind turbines enclosed in modular cages, to convert jet-generated wind into renewable energy. They run autonomously thanks to solar panels and can also be used for trains and cars. A single turbine could produce up to 300 MWh of electricity per year at large airports, reducing traditional energy consumption

@jetwind

There are places where wind is not only predictable but also follows strict patterns. The basic idea behind this new method is simple: tapping the energy produced by jet engines. With the use of the wind produced by airplanes, airports can use it to produce electricity to be used inside terminals.

Energy Capturing Pod

The idea was conceived by Dr. Tarek O. Souryal, a surgeon who developed the concept more than 20 years ago. He proposed tapping airplane-generated wind using Energy Capturing Pods (ECPs), cage-like systems with wind turbines. Since jet engines travel as high as 373 mph, they are a relatively energetic source.

The Energy Capturing Pods are able to capture maximum energy. Each pod is scalable and independent. Additionally, two 550W solar panels are included in each cage to support the system so that each unit operates independently without any external power source. Each generator can produce up to 2 kW.

The energy produced by the pods is electricity that the airport no longer needs to obtain from the grid. It can be distributed to any location within the airport to power electric vehicles or smart devices.

Last December, the first Jet Wind Pods were being installed at Dallas Love Field Airport to capture wind off airplane jet streams. An 18-month test pod was at the airport that witnessed over 10,000 flights. Those statistics were gathered to assist in calibrating the newer models.

Beyond airplanes

The company that invented the technology, Jet Wind, desires to move its revolutionary system out of airports, utilizing artificial wind generated by cars and trains and converting it to renewable energy.

Human activity generates vast amounts of wasted energy every day, says Dr. Souryal. With over 100,000 flights taken worldwide with over 10 million travelers, much of this energy is lost into the air.

One wind turbine such as the one pilot-tested at Dallas Love Field could produce as much as 300 MWh of electricity annually if used at a large airport like Los Angeles International Airport.

Source: JetWind